The AI effect - from Mechanical Turks to Deep Blue

How contradictory we are. On the one hand, we seem to ascribe too much intellectual power where just trickery exists. But we're just as likely to go in a kind of opposite direction, and dismiss a mental achievement once it is revealed as 'mere computation'. That's what the AI effect is all about, and a recent foray into history brought it in sharp focus.

Sometime at the end of the 18th Century, a certain Wolfgang von Kempelen, baron, made an amazing claim- that he had constructed a chess-playing automaton, the Mechanical Turk of the title. He toured Europe with it, and the machine played a wicked game of chess indeed. After Kempelen's death in 1804, the machine was sold to Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, who continued its tours, this time including the Americas. It appears to have been quite a sensation.

Yes, there was a lot of skepticism about its operation. Well-placed, it turns out, as indeed the machine didn't really play chess, so much as provide concealment for a human chess player. It helps to keep things in perspective though, and remember that the technology of automata was fairly well developped in 18th century Europe, and the fact that calculating machines already existed at the time on the continent (Pascal had invented and constructed one in the 17th century, and by the end of that same century Leibniz had constructed a new design), which made somewhat plausible the claim that someone living at that time and place could, somehow, devise an automatic chess master.

But, back to the skepticism. One famous article debunking the Mechanical Turk was written by Poe, published in 1836, and is in its entirety an interesting read providing both the historical context that made the Turk plausible, the summary of reactions to its exhibitions, as well as a list of arguments from Poe as to why the Mechanical Turk wasn't actually mechanical, as in, it was not a pure machine.

Most of those arguments rely on noticing and interpreting various aspects of Mälzel's showsmanship, revealing them as ways to divert attention from the trickery. But two of Poe's arguments are especially interesting, from a history of AI perspective:

Yes, both are quaintly wrong. It's hard to see how Poe let slip "1. Regularity" into his essay, as it's quite obvious that a machine does not need to be fed data regularly; it just needs to be notified that it got data. This was the case with the calculating machines existing in Poe's time, which makes the error jarring. But telling, because it reveals what was associated in the minds of people with the behavior of machines.

Argument 3, "winning strategy", is even more interesting despite its circularity. Poe is implying the concept of winning strategy here, decades before it was formulated by the Theory of Games, and says that if a machine is to play chess, then a machine must play perfect chess. The error is staggering from a modern perspective. Why should he assume that a machine must play good chess? After all, a clock may deliberately point at the wrong hour. Machine behavior does not imply correctness.

Again, the key is to be found in how Poe, and his contemporaries, understand machines. Earlier in the essay he compares Babbage's calculators to the chess player:

Notice also how Poe says that the ability to deal with changing situations and rejudging current states without reaching nor requiring mathematical certainty is the purview of mind.

How far we've come.

Chess playing remained a hallmark of human intelligence for most of the 19th and 20th century ... until it wasn't. Deep Blue won its match against Kasparov in 1997, newer chess engines like Deep Fritz can defeat chess world champions while running on the kind of hardware you may be using right now (and Deep Fritz isn't even the highest ranked automated chess player).

We are no longer wowed by irregular machines that make incomplete plans from incomplete searches, and discard and readjust their work depending on new "surprising" developments. Poker's where it's at now. Or chatbots. Or whatever computers cannot convincingly do. Until they will, when it will be something else.

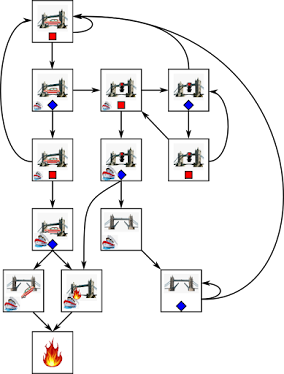

Incidentally, a minor aside here at the end. What about a winning strategy for chess? Without a modification to the rules so as to make all game ends a win for someone, it's not clear that one exists. With a modification to make what in usual chess rules would be called draw to be a win for one player, it's still not clear what the winning strategy looks like. The game tree is just too large to store and use for automated play in the manner that Poe envisioned. The only hope is to try and find some kind of patterns in it, so that one can store some comparatively small pieces of it and use them to achieve perfect play. In fact, one would need to try and analyze the game tree, but would only need to keep those parts that are "near" the winning strategy, or if none exists, the perfect play strategy that also allows draws as a good outcome.

For chess, this hasn't been done yet. But, it has been done for checkers.

Sometime at the end of the 18th Century, a certain Wolfgang von Kempelen, baron, made an amazing claim- that he had constructed a chess-playing automaton, the Mechanical Turk of the title. He toured Europe with it, and the machine played a wicked game of chess indeed. After Kempelen's death in 1804, the machine was sold to Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, who continued its tours, this time including the Americas. It appears to have been quite a sensation.

Yes, there was a lot of skepticism about its operation. Well-placed, it turns out, as indeed the machine didn't really play chess, so much as provide concealment for a human chess player. It helps to keep things in perspective though, and remember that the technology of automata was fairly well developped in 18th century Europe, and the fact that calculating machines already existed at the time on the continent (Pascal had invented and constructed one in the 17th century, and by the end of that same century Leibniz had constructed a new design), which made somewhat plausible the claim that someone living at that time and place could, somehow, devise an automatic chess master.

But, back to the skepticism. One famous article debunking the Mechanical Turk was written by Poe, published in 1836, and is in its entirety an interesting read providing both the historical context that made the Turk plausible, the summary of reactions to its exhibitions, as well as a list of arguments from Poe as to why the Mechanical Turk wasn't actually mechanical, as in, it was not a pure machine.

Most of those arguments rely on noticing and interpreting various aspects of Mälzel's showsmanship, revealing them as ways to divert attention from the trickery. But two of Poe's arguments are especially interesting, from a history of AI perspective:

Edgar Allan Poe: 1. The moves of the Turk are not made at regular intervals of time, but accommodate themselves to the moves of the antagonist — although this point (of regularity) so important in all kinds of mechanical contrivance, might have been readily brought about by limiting the time allowed for the moves of the antagonist. For example, if this limit were three minutes, the moves of the Automaton might be made at any given intervals longer than three minutes. The fact then of irregularity, when regularity might have been so easily attained, goes to prove that regularity is unimportant to the action of the Automaton — in other words, that the Automaton is not a pure machine. [...]

3. The Automaton does not invariably win the game. Were the machine a pure machine this would not be the case — it would always win. The principle being discovered by which a machine can be made to play a game of chess, an extension of the same principle would enable it to win a game — a farther extension would enable it to win all games — that is, to beat any possible game of an antagonist. A little consideration will convince any one that the difficulty of making a machine beat all games, is not in the least degree greater, as regards the principle of the operations necessary, than that of making it beat a single game. If then we regard the Chess-Player as a machine, we must suppose, (what is highly improbable,) that its inventor preferred leaving it incomplete to perfecting it — a supposition rendered still more absurd, when we reflect that the leaving it incomplete would afford an argument against the possibility of its being a pure machine — the very argument we now adduce.

Yes, both are quaintly wrong. It's hard to see how Poe let slip "1. Regularity" into his essay, as it's quite obvious that a machine does not need to be fed data regularly; it just needs to be notified that it got data. This was the case with the calculating machines existing in Poe's time, which makes the error jarring. But telling, because it reveals what was associated in the minds of people with the behavior of machines.

Argument 3, "winning strategy", is even more interesting despite its circularity. Poe is implying the concept of winning strategy here, decades before it was formulated by the Theory of Games, and says that if a machine is to play chess, then a machine must play perfect chess. The error is staggering from a modern perspective. Why should he assume that a machine must play good chess? After all, a clock may deliberately point at the wrong hour. Machine behavior does not imply correctness.

Again, the key is to be found in how Poe, and his contemporaries, understand machines. Earlier in the essay he compares Babbage's calculators to the chess player:

E. A. Poe: But if these machines were ingenious, what shall we think of the calculating machine of Mr. Babbage? What shall we think of an engine of wood and metal which can not only compute astronomical and navigation tables to any given extent, but render the exactitude of its operations mathematically certain through its power of correcting its possible errors? [...] Arithmetical or algebraical calculations are, from their very nature, fixed and determinate. Certain data being given, certain results necessarily and inevitably follow. [...] But the case is widely different with the Chess-Player. With him there is no determinate progression. No one move in chess necessarily follows upon any one other.[...] But in proportion to the progress made in a game of chess, is the uncertainty of each ensuing move. A few moves having been made, no step is certain. Different spectators of the game would advise different moves. All is then dependent upon the variable judgment of the players. Now even granting (what should not be granted) that the movements of the Automaton Chess-Player were in themselves determinate, they would be necessarily interrupted and disarranged by the indeterminate will of his antagonist.[...] It is quite certain that the operations of the Automaton are regulated by mind, and by nothing else. Indeed this matter is susceptible of a mathematical demonstration, a priori.In other words, a mechanical calculator works for problems where the solution depends only on the initial data. Chess, which involves two antagonists, is not such a problem, unless some mechanical procedure exists which renders the antagonist irrelevant; whatever their choice, there's always a determinate choice for the machine to make so as to guarantee victory.

Notice also how Poe says that the ability to deal with changing situations and rejudging current states without reaching nor requiring mathematical certainty is the purview of mind.

How far we've come.

Chess playing remained a hallmark of human intelligence for most of the 19th and 20th century ... until it wasn't. Deep Blue won its match against Kasparov in 1997, newer chess engines like Deep Fritz can defeat chess world champions while running on the kind of hardware you may be using right now (and Deep Fritz isn't even the highest ranked automated chess player).

We are no longer wowed by irregular machines that make incomplete plans from incomplete searches, and discard and readjust their work depending on new "surprising" developments. Poker's where it's at now. Or chatbots. Or whatever computers cannot convincingly do. Until they will, when it will be something else.

Incidentally, a minor aside here at the end. What about a winning strategy for chess? Without a modification to the rules so as to make all game ends a win for someone, it's not clear that one exists. With a modification to make what in usual chess rules would be called draw to be a win for one player, it's still not clear what the winning strategy looks like. The game tree is just too large to store and use for automated play in the manner that Poe envisioned. The only hope is to try and find some kind of patterns in it, so that one can store some comparatively small pieces of it and use them to achieve perfect play. In fact, one would need to try and analyze the game tree, but would only need to keep those parts that are "near" the winning strategy, or if none exists, the perfect play strategy that also allows draws as a good outcome.

For chess, this hasn't been done yet. But, it has been done for checkers.

Comments

Post a Comment