Dark Magics to avoid

If there's anything true of art in general, it's that any rule beginning with "don't" should be broken on occasion. Art should engage the soul, the conscious soul even, and nothing better for that than the occasional thing that's just that bit out of place, that bit unexpected. Conform to every rule you heard and what you produce can be consumed automatically. It's when the rules fail that consciousness kicks in.

So in that spirit, treat the following "don'ts" as guidelines, and even break them-- but make sure you know what you're doing ;) For what follows is a list of magical powers which, if let loose on a plot, stand a good chance to render it hole-y. And the list is by no means exhaustive: feel free to argue for more items to be put on it.

To give a flavor of the disruptive nature of magic, let's look at an example that will NOT kill a story ... but which, the character who suggested it argued, would kill society.

NaN. Invisibility

Glaucon, a wit-sparring partner of Socrates as Plato recounts in the Republic, put forth the story of a ring which conferred invisibility to its wearer. Thus free from the eyes of those who would have punished him otherwise, the wearer took the opportunity to commit any number of crimes. In Glaucon's time, this was a thought experiment meant to show that it is not inner virtue but fear of external reprisal which keeps society functioning. The idea was expanded into a bigger fictional treatment (you might have heard of it, and no it's not that one), and it even gets a lengthy discussion in a book of moral psychology. According to the research, apparently Glaucon was right, Socrates was wrong, and the key to organizing a just society is to make sure people are afraid for their reputations. Invisibility/anonymity prevent knowledge of guilt, which prevents punishment, which protects promises, which enable a social order to function.

Thus, in real life, invisibility would be too dark a magic to allow. In stories though it works just fine (particularly if it strictly means invisibility, as there are ways to circumvent that kind of protection). So this magic is not really on the list (NaN).

But let's get to the list proper.

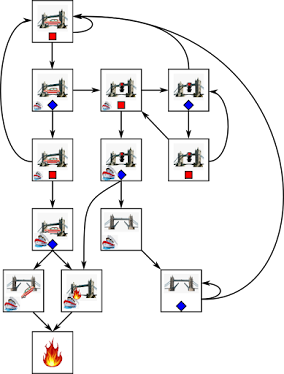

0. Time travel

A classic, and yes, I'm stretching a bit what "magic" means since typically time travel is offered to characters via some sciency-sounding contrivance. But any sufficiently advanced technology, as they say, is magic, and though many have tried time-travel plots, the moment you allow changes to the past you blow up the logical structure of the plot. If you go back in time to change something, and you do, then by the time you need to travel back you won't, because there'd be no reason.

The time travel enthusiast will protest: time travel need not be allowed to change anything (as in Ted Chiang's beautiful Alchemist's Gate), and when it does, maybe it changes things in a parallel universe. But really, is that such a good resolution? Fixing someone else's "you"'s problem, while your own world remains plagued by whatever you went back in time to fix?

Another protest may be that changes need not be abrupt. Indeed, allowing gradual changes only, so that a time loop stabilizes to a consistent history, may offer some interesting computational and narrative perspectives that I think haven't been explored enough yet. Essentially, it's like save-scumming in games: a character fixes a problem by sending messages to their past selves about what to do. When they find the solution, they send it back and enact it as given, thus stabilizing their history.

But most of the time, writers seem to want their characters back in time to fix their own worlds. And in that case, maybe you get something like Looper. It makes no sense that the man from the future would see his body parts disappear as his younger self is tortured (would a legless fugitive even get into a car that needs pedals?). Still a chillingly effective scene, but handle your time paradoxes with care.

1. Prophecy

A very particular form of time travel, one where information comes to you from the future. So often used to the point of eye-rolling cliche in fantasy (is it really that common, really, or is it just perception?), but that's not why it's here. Indeed, usually in fantasy these prophecies are gifted from somewhere else, and you cannot take them as you will. That kind of prophecy is safe for stories.

Imagine however a character with the power to look into another's future at will. Or maybe with a touch, or some other token ritual, but the point remains: all future is there for this character's querying.

Again, maybe if you're Ted Chiang you can pull it off. But unless the point of the story is to illuminate the nature of cognition as it relates to time, unless gaining the ability of prophecy is the climax, then it will kill a story if you think about it. If this character knows everything that will be, how come they didn't know this obviously relevant thing?

No lesser light than Alan Moore fell into this trap for Watchmen. Doctor Manhattan, the one true superhuman, has both transcended the human condition and realized the limits of existence itself. He thinks of himself as a puppet who can see the strings, for every moment of time already exists in an eternal 4D shape of spacetime of which the doctor is aware, unlike the rest of us. It is certainly poetic, and would certainly be workable if Doctor Manhattan was not also a character inside a plot, therefore a character with goals.

But he does, at least allegedly, have goals. He wants to stop another character from doing something bad, and this other character takes measures (some tachyon screening nonsense) to shield their devious plan from Manhattan's gaze. It's such an obvious kludge: the poetic transcendence of Manhattan is dashed. He may see further than we do, but really he's just a human with better binoculars. Regular fog won't stop him, but tachyons will. And how come he didn't realize what would be going on, before and outside the times and places where the villain had their screen? Couldn't the Doctor have seen that?

Watchmen is still a great comic, since it has a lot more going for it than just some adventure plot. But the adventure plot explodes once you allow a god to be an active participant. Either a god for which nothing is concealed or too hard and no adventure plot, or an adventure plot but a being with mortal limits. You cannot have both.

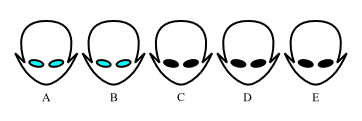

2. Telepathy

In the universe of Star Trek: The Next Generation, we are made aware of the existence of a species (the Betazeds) who are telepathic. They can read minds, as in, know what others are thinking. I've only watched the series, so maybe there's some "expanded universe" lore to clarify more on this, but anyway. There's a race of telepaths. And as luck would have it, a half-Betazed is on the ship we follow along for every episode. She however, being a half-breed, only gets an inkling of the general emotional states of the person she's trying to read.

Why do you think that is?

Imagine if she could in fact read minds completely. "Councillor Troy", Picard asks, as if you needed to speak to a telepath, "what does the man on the screen think?" "He plans to deceive you into lowering the shields. The refugees are actually pirates who plan on hijacking the ship." "Gosh. Well, better move away from here and alert the fleet to their activities." *cue end credits*

How in the name of Vectron didn't the Betazeds come to rule the galaxy is a mystery I don't remember being solved.

But the thing is, a lot of plots rely on deception, or at least incomplete knowledge. Having someone omniscient, or at least telepathic, spoils the entire point of the story, of the chase. The Next Generation illustrates this beautifully in an episode where Geordi and Data are in the Holodeck playing a detective story lifted from the Sherlock Holmes canon. As soon as they meet the first character, Data searches the man to reveal the incriminating evidence he was carrying; because he'd read the story before, you see. Geordi tells him this was missing the point, and tells the computer to create a new Sherlock Holmes story, so that Data could experience the thrill of solving a mystery, not just the banality of knowing the solution.

3. Mind Control

I've seen this done in Saturday morning cartoons (some older animated Batman version), and of course you have scenarios like Invasion of the Bodysnatchers, and various zombification/possession stories. So in that sense, it's common, and has many guises. But I think all these guises are not quite the same thing ...

In a zombification/possession situation, the character being zombified or possessed is, functionally, dead: they have lost their own agency. They're not there. Indeed, it's rare that they can be brought back if they're zombies (and very hard to get them back when they're possessed). Because it makes clear what's being sacrificed, this is a safer form of this dark magic. Also, in such situations it usually comes with rules (how the zombies propagate), genre expectations (survival of the zombie apocalypse is expected to be a culling anyway), or genre expectations (exorcisms tend to be the point of the stories where they happen).

Imagine instead if the power of mind control is given to a character to use at their discretion. Then, essentially, you only have one character. Everyone else is, or is one dubious ray away from being, the puppet of someone else. In the Batman serial, one of the villains would hypnotize or mind control one of the heroes into fighting the other. While this may get nerds moist about what would happen if X and Y fought (even though usually they're on the same side), it's also a hackjob done to the characters and story. There really isn't a reason to have X and Y fighting, and the only way we could stage it is if we killed one of them and populated their husk with something else. This is then also used as a cheap excuse to get a character off scot-free. It's not their fault, you see, they were mind controlled into doing it.

Leave mind control to out-of ideas writers for Saturday morning cartoons. Have your villains influence, cajole, threaten, coerce in more human ways. And have characters who may bemoan the machinery they find themselves a cog in, but always with the theoretical possibility of choosing to snap out.

4. Resurrection

Star Trek, the movies (the recent ones) provide an example of this. In the Wrath of Khaan remake, one of the characters finds himself, basically, dead by radiation poisoning. Fortunately, the blood of an engineered super-human has such a high healing factor that it manages to restore this (nigh?) dead character to life.

So in the next film, of course they had vials of cloned or mass-produced superblood on short call, just in case some trauma victim needed a quick pick me up.

...

Of course they didn't. They "forgot" all about the blood, in an attempt to sweep the consequences under the rug. If you have the ability to bring back anyone from the dead, then nobody can get hurt. Well, they can-- pain is a cruel mistress still-- but it feels less meaningful when there are no irreversible consequences.

The Marvel films are getting criticized for this, on occasion. (I'm sure they cry all the way to the bank.) Basically, nobody important dies. They "die", but swiftly come back. Then where's the danger? We expect, of course, that the protag of an adventure story will be ok by the end, but the threats they face should be credible. In a world with no death, there is, almost, no threat.

Almost. There are fates worse than death, such as enduring torture prolonged by the best life-restoring medicine in the universe. But such a torture, cruel as it sounds, keeps with it the possibility of escape, retribution, and compensation. Death is a one way street to a mystery. Whatever retribution or restoration may await, it's not one for mortal ken. And if no retribution nor restoration await, so much the worse the injustice.

So if you want to jolt the reader and imbue more meaning to the threats facing your characters, remember that when dead, they should stay dead.

----

A common thread emerges from the magics above, which is that they are or should be denied to characters. By which I mean, mortals with aims that intersect the plot. It's quite another to have these powers belong to gods who appear in the story for their own mysterious purposes.

"Mysterious" is a key word there. If a character with known or knowable goals has one of the powers above, then one of the chief problems that it may cause is, "why didn't X use the power Y in situation Z"? Give these powers to characters, and they will game the system to their ends, in ways that often will not line up with the story you want for them. You're then forced to either give in, or invent some hack-job of a limit (Moore, in Watchmen), or just sweep the power under the rug and pretend it never happened (Star Trek).

There is also a sense in which what is appropriate for gods, entities who can reshape being itself, is cheap for mortals. Resurrection plays a big part in one of the greatest stories ever told on Earth: Jesus' life. There's a lot going on there, but one of the morals is, God can rearrange the world so as to write death out of it, for those who follow the path shown (and then there's the usual theist vs atheist argument of whether this is for love or insanity). God can do that, because God can set the parameters of the universe.

The mortal condition is to operate within the parameters of the universe. The stories that feel truer and more meaningful are not therefore those where humans can play fast with the rules. Our lot is to, at best, work around them. And while a new technology is miraculous in the lab, it is mundane in your newest dongle. Perhaps one day we will conquer death, but on that day resurrection will not be miraculous. It's just another of the parameters we work within.

Cheers.

So in that spirit, treat the following "don'ts" as guidelines, and even break them-- but make sure you know what you're doing ;) For what follows is a list of magical powers which, if let loose on a plot, stand a good chance to render it hole-y. And the list is by no means exhaustive: feel free to argue for more items to be put on it.

To give a flavor of the disruptive nature of magic, let's look at an example that will NOT kill a story ... but which, the character who suggested it argued, would kill society.

NaN. Invisibility

Glaucon, a wit-sparring partner of Socrates as Plato recounts in the Republic, put forth the story of a ring which conferred invisibility to its wearer. Thus free from the eyes of those who would have punished him otherwise, the wearer took the opportunity to commit any number of crimes. In Glaucon's time, this was a thought experiment meant to show that it is not inner virtue but fear of external reprisal which keeps society functioning. The idea was expanded into a bigger fictional treatment (you might have heard of it, and no it's not that one), and it even gets a lengthy discussion in a book of moral psychology. According to the research, apparently Glaucon was right, Socrates was wrong, and the key to organizing a just society is to make sure people are afraid for their reputations. Invisibility/anonymity prevent knowledge of guilt, which prevents punishment, which protects promises, which enable a social order to function.

Thus, in real life, invisibility would be too dark a magic to allow. In stories though it works just fine (particularly if it strictly means invisibility, as there are ways to circumvent that kind of protection). So this magic is not really on the list (NaN).

But let's get to the list proper.

0. Time travel

A classic, and yes, I'm stretching a bit what "magic" means since typically time travel is offered to characters via some sciency-sounding contrivance. But any sufficiently advanced technology, as they say, is magic, and though many have tried time-travel plots, the moment you allow changes to the past you blow up the logical structure of the plot. If you go back in time to change something, and you do, then by the time you need to travel back you won't, because there'd be no reason.

The time travel enthusiast will protest: time travel need not be allowed to change anything (as in Ted Chiang's beautiful Alchemist's Gate), and when it does, maybe it changes things in a parallel universe. But really, is that such a good resolution? Fixing someone else's "you"'s problem, while your own world remains plagued by whatever you went back in time to fix?

Another protest may be that changes need not be abrupt. Indeed, allowing gradual changes only, so that a time loop stabilizes to a consistent history, may offer some interesting computational and narrative perspectives that I think haven't been explored enough yet. Essentially, it's like save-scumming in games: a character fixes a problem by sending messages to their past selves about what to do. When they find the solution, they send it back and enact it as given, thus stabilizing their history.

But most of the time, writers seem to want their characters back in time to fix their own worlds. And in that case, maybe you get something like Looper. It makes no sense that the man from the future would see his body parts disappear as his younger self is tortured (would a legless fugitive even get into a car that needs pedals?). Still a chillingly effective scene, but handle your time paradoxes with care.

1. Prophecy

A very particular form of time travel, one where information comes to you from the future. So often used to the point of eye-rolling cliche in fantasy (is it really that common, really, or is it just perception?), but that's not why it's here. Indeed, usually in fantasy these prophecies are gifted from somewhere else, and you cannot take them as you will. That kind of prophecy is safe for stories.

Imagine however a character with the power to look into another's future at will. Or maybe with a touch, or some other token ritual, but the point remains: all future is there for this character's querying.

Again, maybe if you're Ted Chiang you can pull it off. But unless the point of the story is to illuminate the nature of cognition as it relates to time, unless gaining the ability of prophecy is the climax, then it will kill a story if you think about it. If this character knows everything that will be, how come they didn't know this obviously relevant thing?

No lesser light than Alan Moore fell into this trap for Watchmen. Doctor Manhattan, the one true superhuman, has both transcended the human condition and realized the limits of existence itself. He thinks of himself as a puppet who can see the strings, for every moment of time already exists in an eternal 4D shape of spacetime of which the doctor is aware, unlike the rest of us. It is certainly poetic, and would certainly be workable if Doctor Manhattan was not also a character inside a plot, therefore a character with goals.

But he does, at least allegedly, have goals. He wants to stop another character from doing something bad, and this other character takes measures (some tachyon screening nonsense) to shield their devious plan from Manhattan's gaze. It's such an obvious kludge: the poetic transcendence of Manhattan is dashed. He may see further than we do, but really he's just a human with better binoculars. Regular fog won't stop him, but tachyons will. And how come he didn't realize what would be going on, before and outside the times and places where the villain had their screen? Couldn't the Doctor have seen that?

Watchmen is still a great comic, since it has a lot more going for it than just some adventure plot. But the adventure plot explodes once you allow a god to be an active participant. Either a god for which nothing is concealed or too hard and no adventure plot, or an adventure plot but a being with mortal limits. You cannot have both.

2. Telepathy

In the universe of Star Trek: The Next Generation, we are made aware of the existence of a species (the Betazeds) who are telepathic. They can read minds, as in, know what others are thinking. I've only watched the series, so maybe there's some "expanded universe" lore to clarify more on this, but anyway. There's a race of telepaths. And as luck would have it, a half-Betazed is on the ship we follow along for every episode. She however, being a half-breed, only gets an inkling of the general emotional states of the person she's trying to read.

Why do you think that is?

Imagine if she could in fact read minds completely. "Councillor Troy", Picard asks, as if you needed to speak to a telepath, "what does the man on the screen think?" "He plans to deceive you into lowering the shields. The refugees are actually pirates who plan on hijacking the ship." "Gosh. Well, better move away from here and alert the fleet to their activities." *cue end credits*

How in the name of Vectron didn't the Betazeds come to rule the galaxy is a mystery I don't remember being solved.

But the thing is, a lot of plots rely on deception, or at least incomplete knowledge. Having someone omniscient, or at least telepathic, spoils the entire point of the story, of the chase. The Next Generation illustrates this beautifully in an episode where Geordi and Data are in the Holodeck playing a detective story lifted from the Sherlock Holmes canon. As soon as they meet the first character, Data searches the man to reveal the incriminating evidence he was carrying; because he'd read the story before, you see. Geordi tells him this was missing the point, and tells the computer to create a new Sherlock Holmes story, so that Data could experience the thrill of solving a mystery, not just the banality of knowing the solution.

3. Mind Control

I've seen this done in Saturday morning cartoons (some older animated Batman version), and of course you have scenarios like Invasion of the Bodysnatchers, and various zombification/possession stories. So in that sense, it's common, and has many guises. But I think all these guises are not quite the same thing ...

In a zombification/possession situation, the character being zombified or possessed is, functionally, dead: they have lost their own agency. They're not there. Indeed, it's rare that they can be brought back if they're zombies (and very hard to get them back when they're possessed). Because it makes clear what's being sacrificed, this is a safer form of this dark magic. Also, in such situations it usually comes with rules (how the zombies propagate), genre expectations (survival of the zombie apocalypse is expected to be a culling anyway), or genre expectations (exorcisms tend to be the point of the stories where they happen).

Imagine instead if the power of mind control is given to a character to use at their discretion. Then, essentially, you only have one character. Everyone else is, or is one dubious ray away from being, the puppet of someone else. In the Batman serial, one of the villains would hypnotize or mind control one of the heroes into fighting the other. While this may get nerds moist about what would happen if X and Y fought (even though usually they're on the same side), it's also a hackjob done to the characters and story. There really isn't a reason to have X and Y fighting, and the only way we could stage it is if we killed one of them and populated their husk with something else. This is then also used as a cheap excuse to get a character off scot-free. It's not their fault, you see, they were mind controlled into doing it.

Leave mind control to out-of ideas writers for Saturday morning cartoons. Have your villains influence, cajole, threaten, coerce in more human ways. And have characters who may bemoan the machinery they find themselves a cog in, but always with the theoretical possibility of choosing to snap out.

4. Resurrection

Star Trek, the movies (the recent ones) provide an example of this. In the Wrath of Khaan remake, one of the characters finds himself, basically, dead by radiation poisoning. Fortunately, the blood of an engineered super-human has such a high healing factor that it manages to restore this (nigh?) dead character to life.

So in the next film, of course they had vials of cloned or mass-produced superblood on short call, just in case some trauma victim needed a quick pick me up.

...

Of course they didn't. They "forgot" all about the blood, in an attempt to sweep the consequences under the rug. If you have the ability to bring back anyone from the dead, then nobody can get hurt. Well, they can-- pain is a cruel mistress still-- but it feels less meaningful when there are no irreversible consequences.

The Marvel films are getting criticized for this, on occasion. (I'm sure they cry all the way to the bank.) Basically, nobody important dies. They "die", but swiftly come back. Then where's the danger? We expect, of course, that the protag of an adventure story will be ok by the end, but the threats they face should be credible. In a world with no death, there is, almost, no threat.

Almost. There are fates worse than death, such as enduring torture prolonged by the best life-restoring medicine in the universe. But such a torture, cruel as it sounds, keeps with it the possibility of escape, retribution, and compensation. Death is a one way street to a mystery. Whatever retribution or restoration may await, it's not one for mortal ken. And if no retribution nor restoration await, so much the worse the injustice.

So if you want to jolt the reader and imbue more meaning to the threats facing your characters, remember that when dead, they should stay dead.

----

A common thread emerges from the magics above, which is that they are or should be denied to characters. By which I mean, mortals with aims that intersect the plot. It's quite another to have these powers belong to gods who appear in the story for their own mysterious purposes.

"Mysterious" is a key word there. If a character with known or knowable goals has one of the powers above, then one of the chief problems that it may cause is, "why didn't X use the power Y in situation Z"? Give these powers to characters, and they will game the system to their ends, in ways that often will not line up with the story you want for them. You're then forced to either give in, or invent some hack-job of a limit (Moore, in Watchmen), or just sweep the power under the rug and pretend it never happened (Star Trek).

There is also a sense in which what is appropriate for gods, entities who can reshape being itself, is cheap for mortals. Resurrection plays a big part in one of the greatest stories ever told on Earth: Jesus' life. There's a lot going on there, but one of the morals is, God can rearrange the world so as to write death out of it, for those who follow the path shown (and then there's the usual theist vs atheist argument of whether this is for love or insanity). God can do that, because God can set the parameters of the universe.

The mortal condition is to operate within the parameters of the universe. The stories that feel truer and more meaningful are not therefore those where humans can play fast with the rules. Our lot is to, at best, work around them. And while a new technology is miraculous in the lab, it is mundane in your newest dongle. Perhaps one day we will conquer death, but on that day resurrection will not be miraculous. It's just another of the parameters we work within.

Cheers.

Absolutely dead on target. Particularly as to time travel: if the characters ever get it under control, the plot falls apart. It only works if it's quirky and unreliable (Back to the Future), absurdly limited in its parameters, or otherwise kept out of the hands of the characters whose actions we're trying to understand.

ReplyDeleteBut an even better point is the one about mind control. To my mind, a story is all about what the characters do, the choices they make. In a mind-control plot, the characters' ability to act is eliminated. Their choices become boring, because they aren't choices; as you remark, the character didn't *do* it.

Great stuff!

Rick

Thanks!

DeleteThe mind control issue is also one I feel strongly about, though I can't seem to muster an argument against it (it's imo the weakest part of the post). There are times where one kills characters left and right, or at least robs them of agency, that seem perfectly fine. Make it a raygun, not a zombie plague however, and something seems to snap into "don't do this" territory. And I don't think it's just that a character is given the power, either.

It might also be what the mind controlled can do. A zombie is a zombie. A possessed person may taunt one about their relatives' activities. But a mind controlled Batman could do anything Batman could do, while not being Batman. It just feels so wrong.

Cheers.

This is a great read. One comment about the Dr. Manhattan bit; he can't see all future, only his own, so while he can see that he can't see the future after a certain point, he can't see the other character setting it up. That was the explanation for why he didn't immediately figure it out, anyway. So, I guess the really big question is, once we get past that moment the tachyon screen exists, shouldn't he know the future from that point? But that doesn't really seem to be the case...

ReplyDeleteAnyway, great read.

Thank you.

DeleteYes, I suppose with enough caveats you might get the Dr. Manhattan situation to work, but it's at least inelegant. There's a lot of stitching needed, for example the screen isn't active where the bad stuff happens and Manhattan should know when it did happen (which was the villain's twist) since he'd been there.

Cheers.

That's interesting, because either in the movie or the comic, I believe the bad stuff is what makes the screen, but it's been a while.

DeletePS. Am totally heartbroken that the Merchant and the Alchemist's Gate is out of print with no digital options. You got me all stoked to read it, particularly when I found out Ted Chiang wrote the story behind Arrival.

On Merchant.., it's another short story (just like "Story of your life", which Arrival is based on). In my case, I read it in a German version of the "Story of your life" collection, so maybe there's an English version of that collection that has it as well.

DeleteIt's a good read, imo, worth the trouble to inquire at the local library or old book store ;)

Cheers.